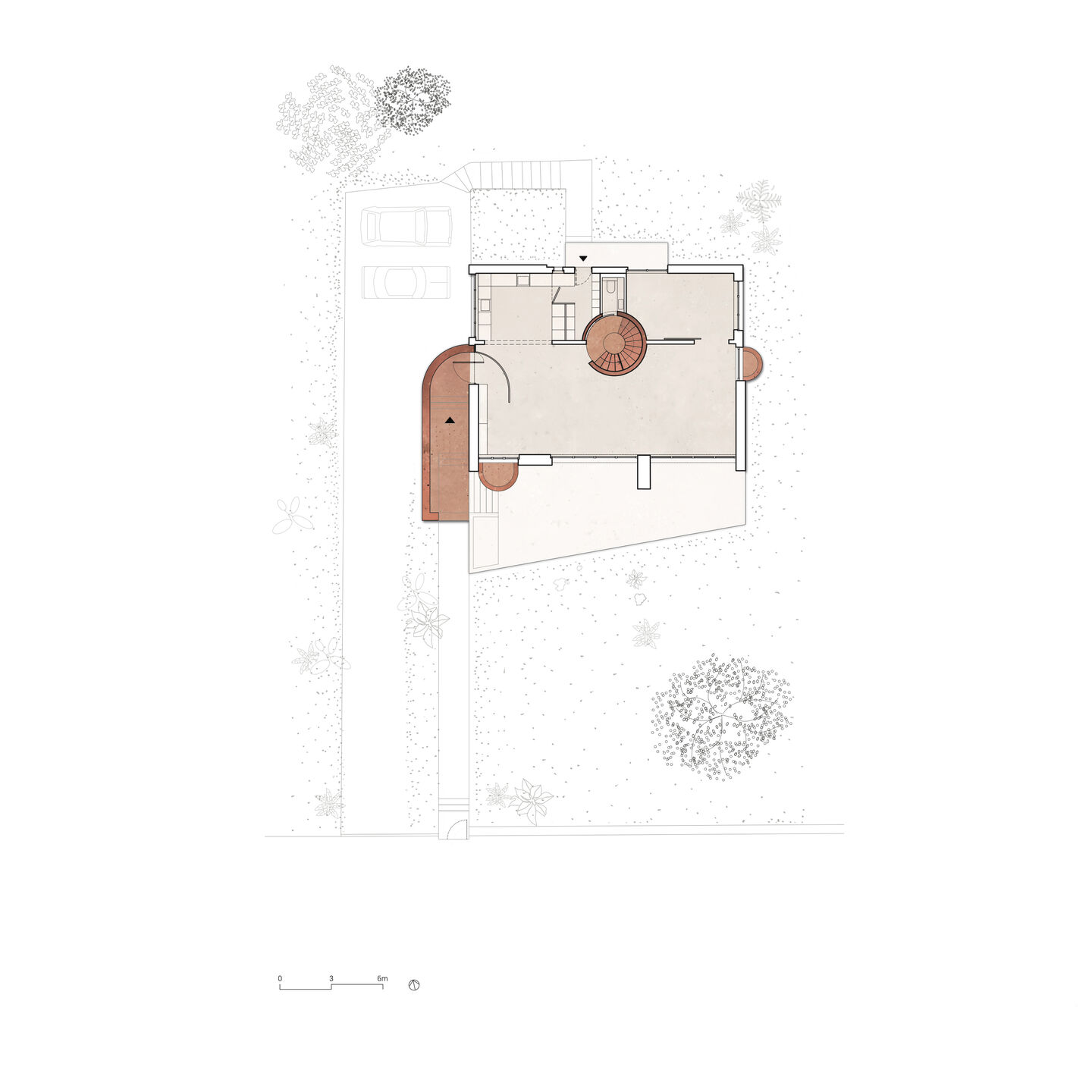

Paris-based Atelier Delalande Tabourin (ADT) has completed the rehabilitation of a 300-square-meter (3,229-square-feet) house located in a 1950s residential area of the town of Versailles. ADT introduced four architectural interventions to the home’s dark interior: four “wells” — for lighting and circulation — that pierce the existing floors and act as distinctive features around which spaces are articulated. These new additions are made with concrete chamotte (grog), a material obtained from the crushed shards of defective bricks. Externally, the home’s heavy cubic appearance is lightened by a series of brick stelae on its sober facade. ADT’s work on materiality achieves a sensitive dialogue between the new architectural interventions and existing brick stelae.

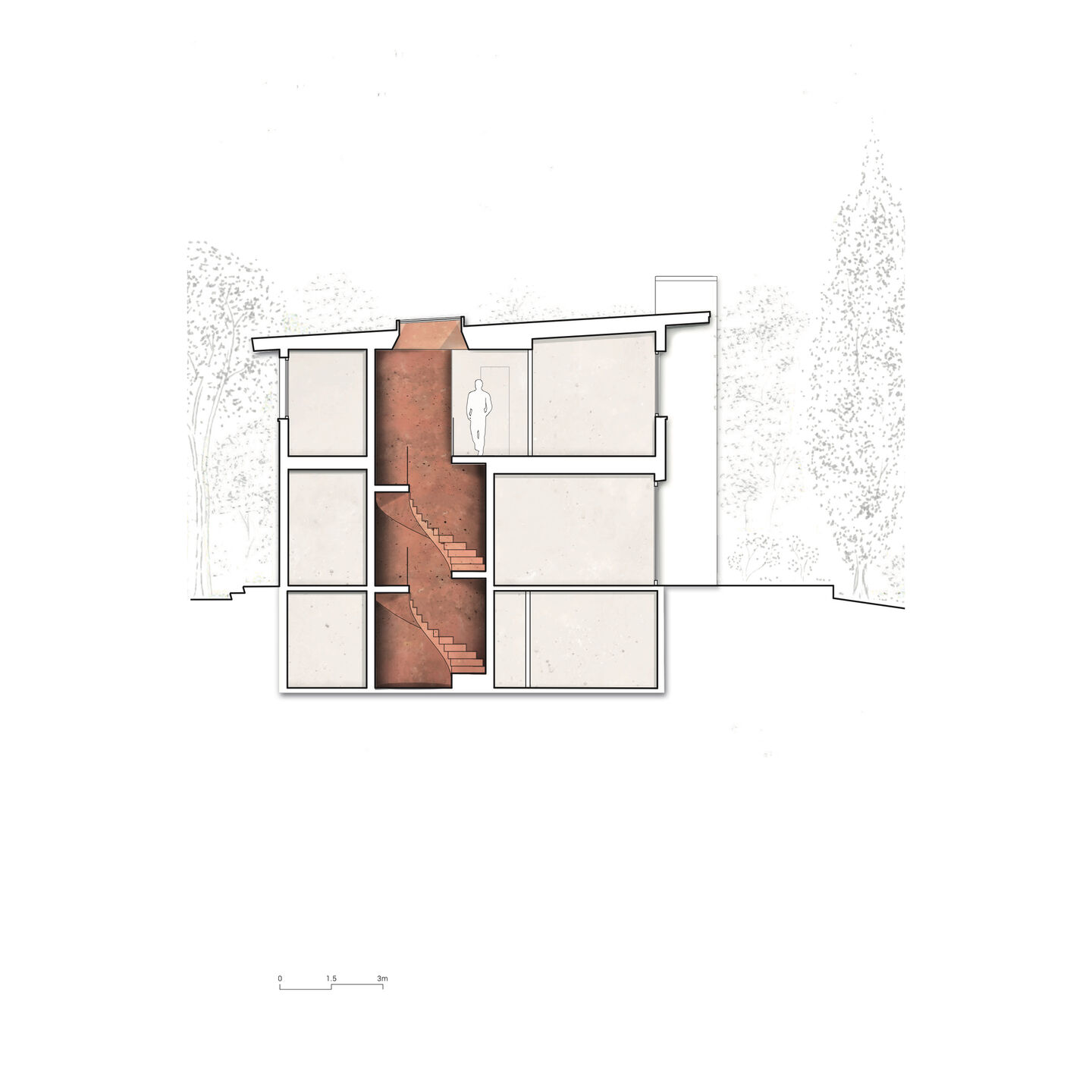

This section model shows the project’s various material interventions. Clockwise from left: entrance, main staircase, and basement skylight.

Atelier Delalande Tabourin was founded in 2017 by architects Nicolas Delalande and Sébastien Tabourin. In its architectural practice, the studio is keen to focus more on the contextualization of materials than a specific quest for form or visual identity. ADT prefers to work with local geological materials and crafts, paying particular attention to their reuse.

Architectural interventions

When first discovering the home’s interior, ADT found a confusing distribution of rooms, with living spaces disconnected from a generous peripheral garden and an underutilized basement isolated from the rest of the property. Sébastien Tabourin explains that the concept behind the project is a simple one: “In their request to refurbish their house, the clients asked that we add more value to the basement — until that point, it had not been used in any meaningful way. The house is very cubic in its form and had limited circulation between each level as well as a rather dark interior atmosphere. We felt that perforating the building with large tubes — used for circulation or light or both — would be the best response.”

Each one the four architectural interventions has a specific relationship with how the house is used. “The first, located at the entrance, is designed to improve the entry sequence to the house, whether on foot from the garden or by car,” explains Tabourin.

“The large central well is the centerpiece, providing access to all levels. Its location was chosen to optimize the home’s layout and to minimize the amount of work required to rebuild the structure. We ensured this well would be visible from every important room. It's the star attraction in the living room, for example. With its large roof window, the well also acts as a skylight to illuminate the space and a thermal regulator to heat or cool different areas, thanks to its high thermal inertia.” This central well connects the home’s basement directly with its upper levels, making it both fully accessible and usable.

Concrete chamotte

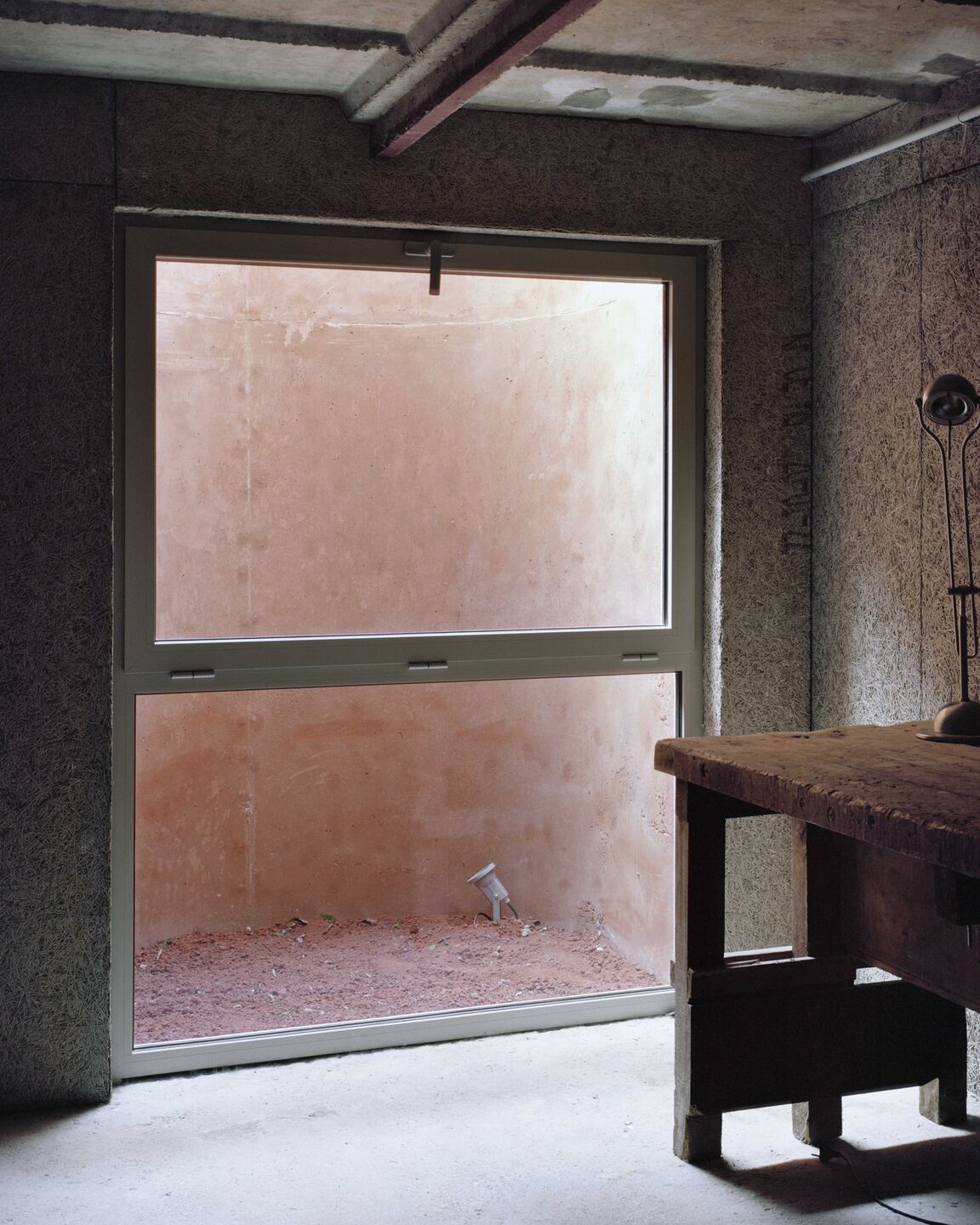

The concrete chamotte used by ADT is a material extension of the existing brick stelae on the home’s facade. It offers “a striking contemporary intervention that respects and interacts with the existing character of the house,” says Tabourin.

The brick material used in the project (referred to as “grogs”) comes from Briqueterie Dewulf, a brick factory in Allonne, northern France. “This brickworks sets aside its unsold, poorly shaped, or over-fired bricks to be crushed,” says Tabourin. “We visited the brickworks to think about working with bricks, not necessarily this waste product. However, when we saw the size of the pile that the waste represented, we knew that we had to start with this material for the project.”

Accumulation of brick waste at Briqueterie Dewulf.

Following the decision to use the brick waste, as part of a “resource analysis” phase, ADT conducted a long series of tests and worked on various prototypes with designer and researcher Anna Saint Pierre (who created Granito, a recycled terrazzo flooring product made by repurposing various fragments of previously used granite). Testing was undertaken in collaboration with the Cemex and Sols companies in order to decide on the “granulometry” (particle-size distribution) of the interior and exterior flooring. Tabourin notes that it would be “almost impossible” to use the chamotte in a public contract owing to the difficulty in finding technical advice. “Outside, the floors are exposed to the rain,” he says. “We know, as does the client, that some of the ‘nuggets’ will disappear over time.”

Prototypes of the choice of concrete chamotte for indoor and outdoor floors.

Asked about any particular advantages versus disadvantages in using chamotte in a project such as this one, Tabourin says: “It does become complicated in some applications, for example, with underfloor heating or structural concrete. The percentage of non-standard aggregates in concrete varies from country to country. It is particularly limited in France: 3 percent of aggregates compared with 33 percent in Belgium. This explains why we had to add a natural binder — taken from the same brickworks and chamotte — in order to achieve the right color for the brick.”

As part of the home’s rehabilitation, ADT experimented with the density of the chamotte as a way of subtly indicating different spatial sequences to residents. “Working with Anna Saint Pierre, we wanted to play with the density of the fireclay in the floors, to create a distinctive graphic effect in the living spaces,” says Tabourin. “Each room has a 40-centimeter-wide decorative border. Sometimes this border identifies a space, such as an office in a bedroom or the kitchen in the main living area of the house.”

Different types/combinations of chamotte were used on the interior and exterior. The light wells are made from a chamotte structural concrete (3 percent chamotte) and natural coloring obtained by finely crushing the chamotte. The outside floors are made with bush-hammered concrete, a process that reveals small spots of chamotte and ensures the surfaces are non-slip. The interior floors use the same concrete as those on the exterior and have a polished finish.

In-situ recycling

In her work, Anna Saint Pierre talks about “in-situ recycling” — such as reusing the home’s existing travertine floors — and strongly emphasizes preserving the history of a place, something that is translated through the project’s materiality. “Anna and I share a love of ancient history, with a penchant for antiquity,” says Tabourin. “As well as using chamotte to reveal traces of the old partitions in the parquet flooring, we reused the travertine tiles from the living room as a bench for the sitting room. We also repurposed brick from the existing house in a Roman spolia style for a concrete washbasin top. We would like to have crafted more small made-to-measure pieces of furniture from recycled materials, however the client wasn't keen on the idea.”

Sustainability

Renovating and rehabilitating this house, as opposed to demolishing and replacing it, as well as using chamotte concrete for new additions (in effect, unwanted brick rubble), will have in all likelihood translated into a carbon saving. Putting this to Sébastien Tabourin, he answers, with sincerity, “I think so, but only very slightly.” He continues: “It's still concrete and we have touched the structure of the house. The eco-responsible ideal would have been to leave the house untouched and to live in it as it was. However, it would have been a complicated house to occupy because the layout was designed for a 1970s lifestyle.

Within architecture, there is an obvious balance to strike between the needs of the user and wider ecological concerns. Tabourin explains that as a practice, ADT “favors the maximum level of respect for what is already there, developing eco-responsible and virtuous architecture, [while remembering] the filter of beauty and spatial emotion.” He adds, that as a young architectural practice, “there's still a lot to learn and explore.”

ADT’s contemporary rehabilitation of this house in Versailles explores the sensory qualities of materiality. The introduction of lighting and circulation wells and respectful use of concrete chamotte, brings a spatial and emotional quality to the home, making it both livable and usable.